RESTORATION OF KĀINGA

tino rangatiratanga o ratou kāinga

If you’re not part of the solution,

you’re part of the problem

Vision: Restoration of Kāinga

This is a simple plan. Restore and rebuild kāinga. It’s a back-to-the-land proposal, a return to ancestral whenua in the 21st century.

Can we speak frankly? The Crown will never have a solution for the problems facing Māori. They tried war, then they tried Urbanisation. Now they try to integrate Māori into Crown governance, creating a Māori elite controlled by Crown dollars. Meanwhile rural Māori live in poverty. Their best and brightest are scattered far and wide, only coming home for tangi and the occasional hui.

Until recently, the elements required to rebuild kāinga were not there. The vision was there, but the practicalities were missing. The talented young families who would return to join their elders in kāinga need proper homes from day one. They need to continue to earn an income to provide for their families. The banks don’t provide construction loans or mortgages, so no home. And the region has no jobs, so no income.

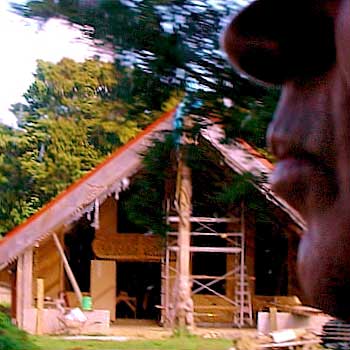

But with the affordable housing crisis a new industry emerged in NZ. Factories making mobile homes, about the size of the traditional wharepuni – the small family home in a traditional kāinga. And high-speed broadband has vanquished the tyranny of distance. Post-COVID, employers are open to remote working. Now, with Starlink, broadband can come to the most remote kāinga even if the government has not installed fibre cables.

A kāinga movement is not Crown sponsored, it is based on tino rangatiratanga. To understand what this means, begin by reading the Te Reo Māori version of Te Tiriti (read here) and focus on what it actually says, not what Crown-paid academics, judges and experts says it means.

In European Law of the State, Te Tiriti is a clear statement of extraterritoriality. Extraterritoriality, usually as the result of negotiations between equal parties, identifies land within the sovereign’s realm that is exempt from the jurisdiction of national law. In Te Tiriti, the Crown agrees to tino rangatiratanga over land and villages within the hapū’s jurisdiction. What’s stopping you?

You have the land. You have the people. You have the governance model (hui moderated by your rangatira). You have the memory of how kāinga work and how they are built. Like your ancestors, you adapt modern technology to serve you, but you remember who you are. As on a waka, everyone has a role to play and all work as one.

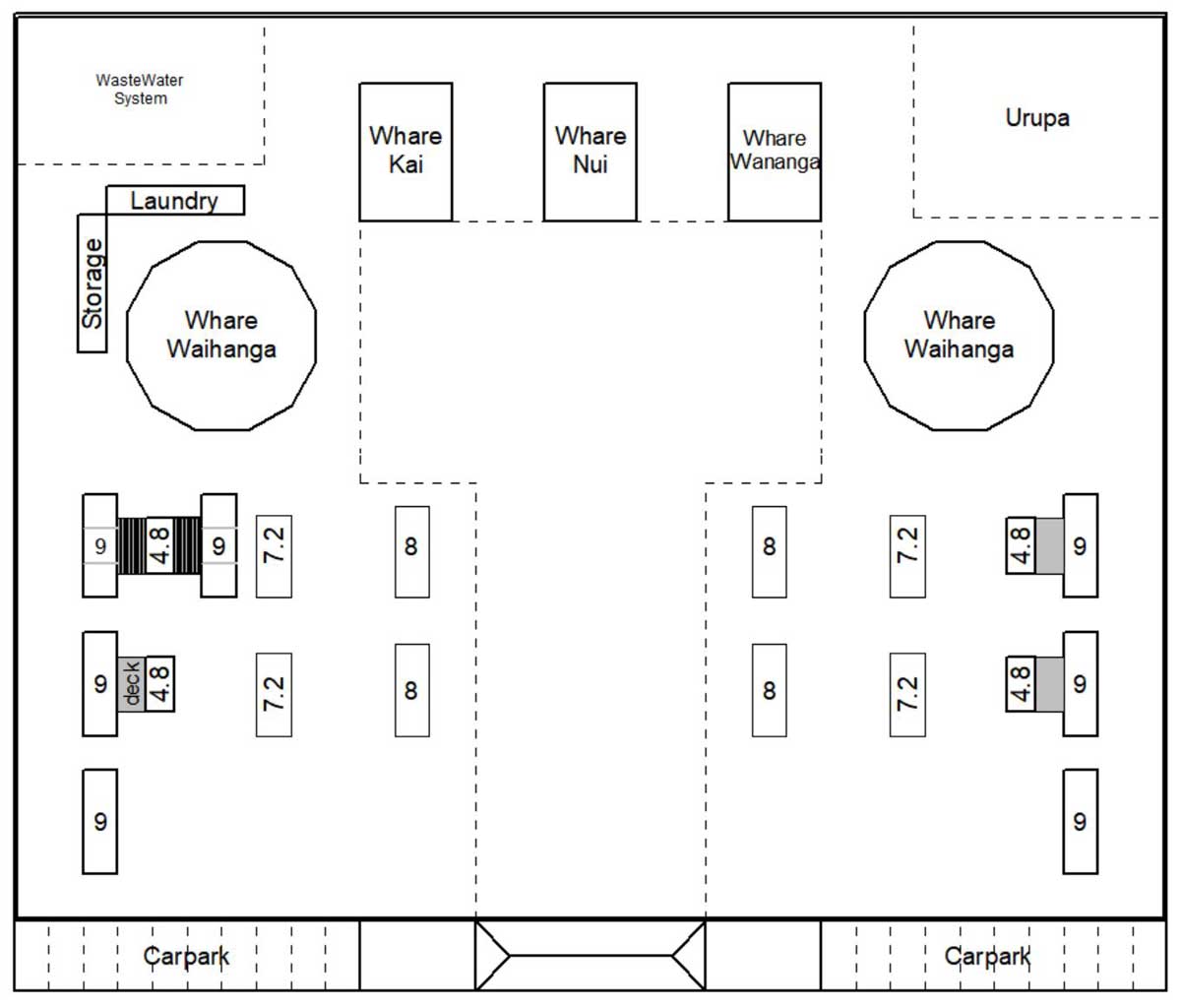

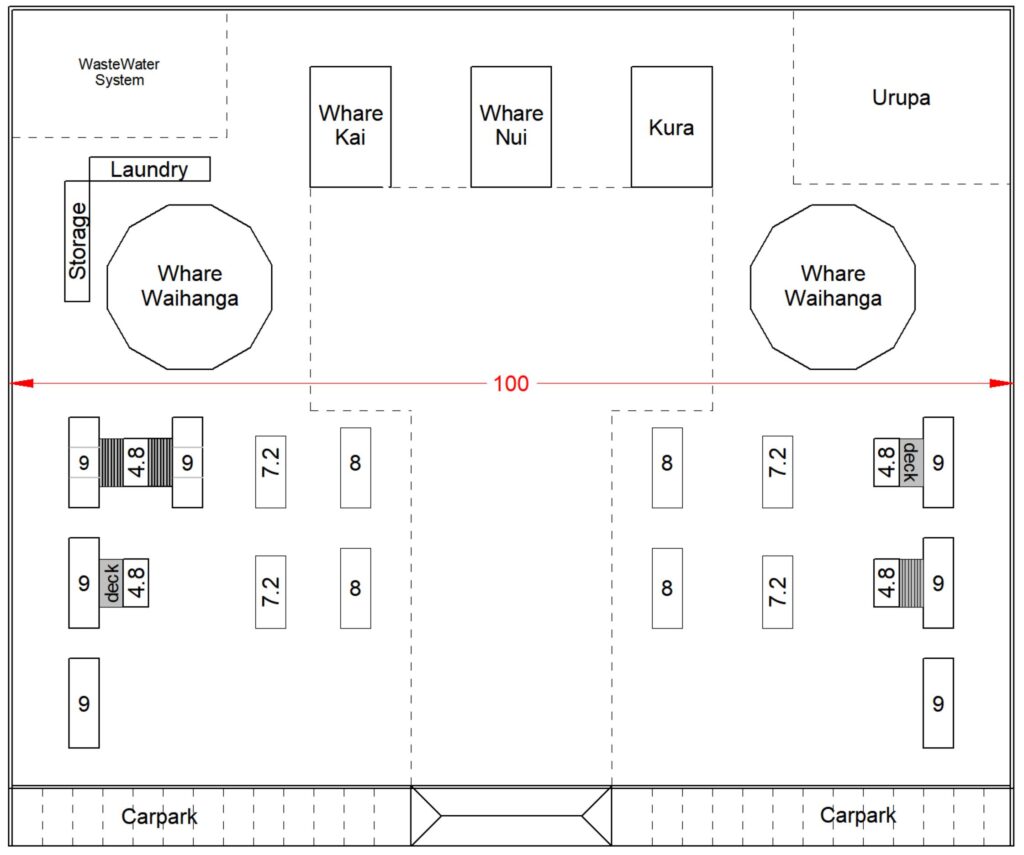

The design of a kāinga

Wharepuni: Think of a marae, then add wharepuni, the small family homes that make the kāinga a living community. Unlike Pākehā housing designed for a relatively isolated nuclear family, wharepuni are smaller because they are part of a larger shared community. Families sleep in their wharepuni, and enjoy private time, but their social time outside is greater. The shared space is their living room.

Whare Waihanga: Then add the whare whaihanga, the workshops that enable the whanau to earn a living. The traditional whare whaihanga were carving and weaving workshops, but today there are many other businesses as well. Think of them as the economic engines of the kāinga.

Kura: Children are hardwired to learn from role models. If role models are gangs, they become gangsters. If TikTok, they steal cars. Living in a kāinga surrounded by mature adults, they become responsible, participating adults, not addicted to drugs & alcohol, not having babies too young.

Immediate Wharepuni

These wharepuni are made in factories where they are also called mobile homes or tiny homes on wheels: Typically 8-9m long, 3m wide with kitchenette, bathroom, lounge and bedroom, these units are designed to be towed behind a 3,500 kg-rated SUV or ute. They install on site within a couple hours and they are parked on land, not fixed to foundations.

With conventional plumbing or composting, they use caravan-type connections not requiring licensed professional to install. Well-designed cabins are double-glazed, warm, dry and durable.

The Maori Village (Kāinga)

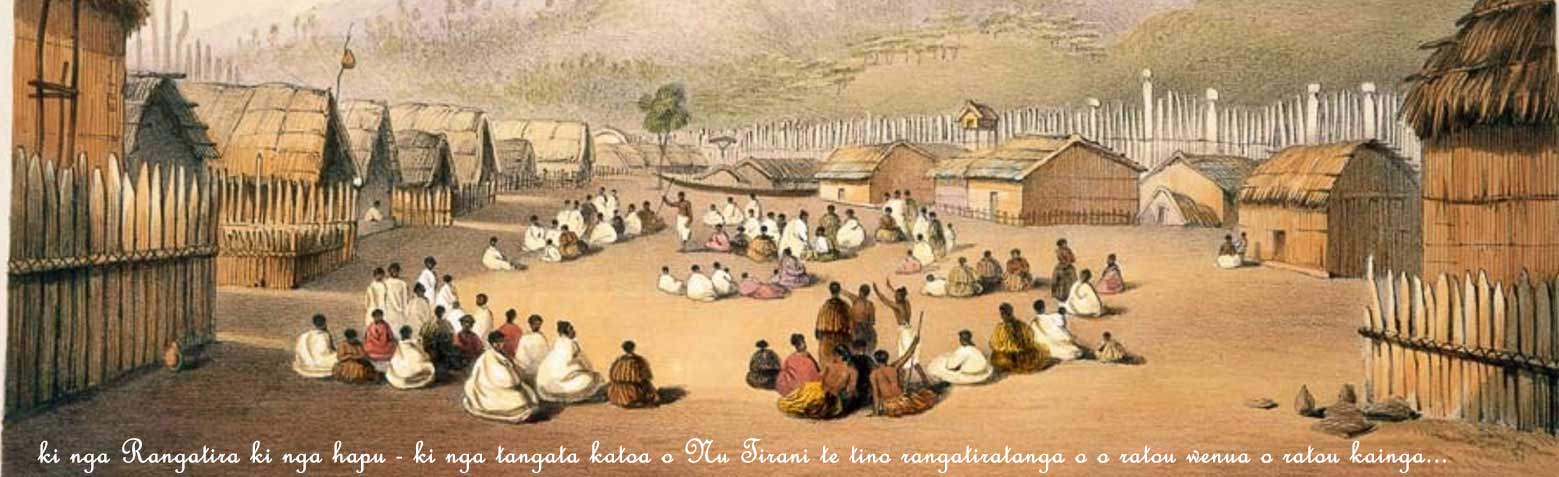

One of the fundamental bases on which any society is organised is that of locality, since certain spatial relations are inherent in the very nature of every group, whether settled or migratory. And the great importance of association in common locality is that it represents not merely a physical fact, but also leads to the formation of a whole body of psychological bonds, due to the common interests of the members and their contact in everyday life. Among the Maori the local group, patent to the eye of every observer, is the village.

Raymond Firth, 1929 Economics of the New Zealand Maori, p91 R.E. Owen, Govt. Printer, Wellington

As Firth observed almost a century ago, kāinga is more than a collection of people who happen to live next to each other. Due to their common interests and contact in everyday life, they form strong psychological bonds.

The 1960’s experiment in urbanisation that enticed young Māori to move to the cities, especially Auckland, broke those bonds. The three attractions of money, jobs and pleasure drew away the young, and as the elders died off, the kāinga fell into ruin.

The breakage is evident in the daily routine of life. Waking up in a single-family home and after breakfast with the kids, hopping in the car or catching a bus, to go to work, is not the same as working in the community with whanau. Sending the children to school cut off from the role models of the whanau adults deprives them of the most important aspect of learning. Knowing how to read is important, but understanding why adults need to know how to read provides the incentive to learn. And then in the elder years, segregating the old people in retirement homes breaks the chain of culture, because it is the elders to pass culture on to the young.

In urbanised society, and in poverty-stricken rural life, teens form their own peer groups. With the introduction of technology, they develop anti-social behaviour that becomes a pathway to prison when they come of age. Car theft and ram raids are role modelled on apps like Tiktok, because these teens and even pre-teens have no supportive kāinga that would offer them a pathway to adulthood.

In urbanised society, and in poverty-stricken rural life, teens form their own peer groups. With the introduction of technology, they develop anti-social behaviour that becomes a pathway to prison when they come of age. Car theft and ram raids are role modelled on apps like Tiktok, because these teens and even pre-teens have no supportive kāinga that would offer them a pathway to adulthood.

All of this is reversed with the restoration of kāinga. At first it may prove challenging to make the kāinga economically self-supporting, but that should be the goal. Work to develop tūrangawaewae, becoming independent of government welfare payments. Work toward true tino rangatiratanga.

In 1840 at Waitangi

Of paramount importance to the rangatira was the kāinga. A kāinga is more than a collection of homes. It is a complete community that included not only the wharenui and wharekai found on today’s marae, but wharepuni – small family homes as well as whare whaihanga – workshops that were the basis of a thriving local economy.

In these kāinga, every adult worked. There was no such thing as unemployment or living on the benefit. Tūrangawaewae stands tall on kāinga, where all are empowered and connected. The kāinga is the foundation, the centre of ones universe, one’s home, and for this reason, along with whenua and taonga katoa, it was the paramount value the Crown promised to protect in exchange for kāwanatanga over Nu Tirani. That promise was breached, but not forgotten. It’s time to remember, to restore mana whenua and mana kāinga.

In 2024 in Aotearoa

The need to restore kāinga is not nostalgia but an economic imperative. Rural Māori suffer poverty, deprivation and a lack of opportunity.

In the 1960’s the Crown began a policy of urbanisation – actively enticing young Māori to leave their kāinga and move to the bright lights, jobs and opportunities of the towns and cities, most notably Auckland. Once Were Warriors demonstrates the adverse effects of this diaspora.

The kāinga system collapsed. The whenua remains, the elders know the stories, but the kāinga exists in memory only. In some cases it remains as a marae – an acre of fenced land with a carpark outside, wharenui, wharekai and marae atea. But no community within, no wharepuni, no whare whaihanga, no thriving economic and social community. The vision of a Renaissance Aotearoa is to restore those kāinga.

©2024 Renaissance Aotearoa Foundation